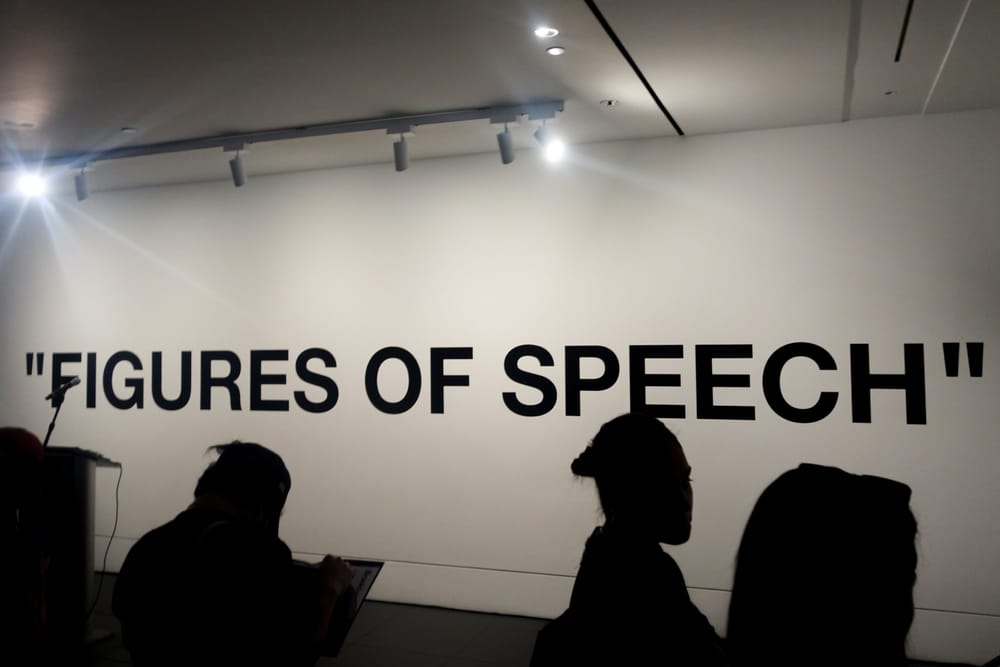

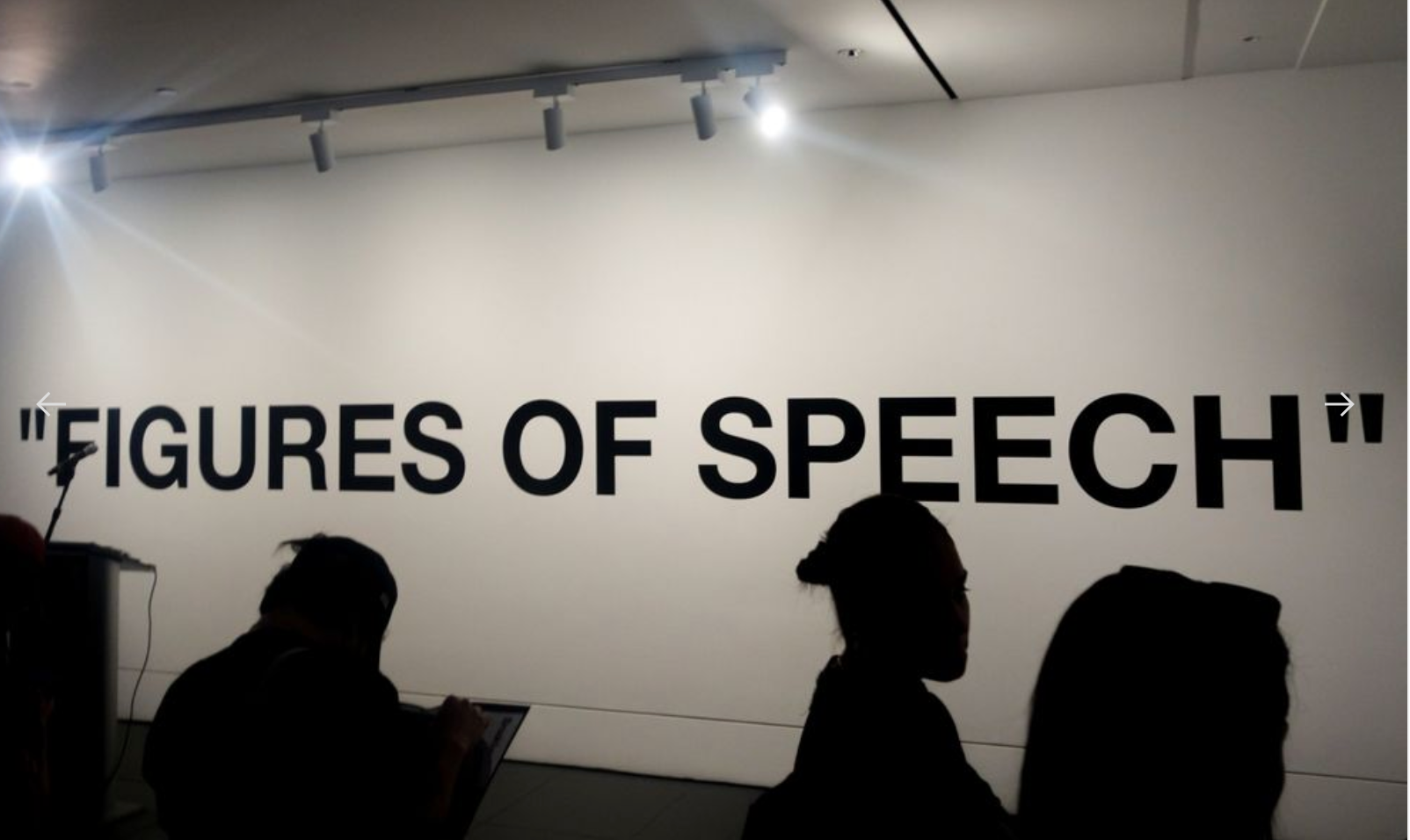

Virgil Abloh's Careful Attention to "Figures of Speech" at Brooklyn Museum

Virgil Abloh was a curious tinkerer who streamlined his multifold of interests with care, attention and a subversive worldview. His legacy-making “Figures of Speech” retrospective has just landed at the Brooklyn Museum following its inception at MCA Chicago back in 2019 with previous stops at Atlanta’s High Museum of Art, ICA Boston as well as Qatar’s Garage Gallery at the Fire Station. It’s clear that there’s a global appreciation for Abloh’s multidisciplinary practice.

What’s makes Brooklyn Museum’s “Figures of Speech” iteration stand out from previous iterations, however, is the minimalist approach that Virgil implemented in the overall format as he worked with the curator and author, Antwaun Sargent to create a show that prides itself in accessibility rather than creating confines in the various genres he played with: Fashion, Art, Design, Architecture, etc. And while Brooklyn’s show is a tighter and smaller curation than the ones he launched before, the structuring for this one offers a more intimate connection for viewers of all kinds of backgrounds. Yes, post-mortem decisions were implemented by his Alaska Alaska creative studio team headed by Tawanda Chiweshe, Sargent and sponsors involved such as Braun, but what makes the show special is its simplicity which Virgil determined at the onset of planning stages.

The ["social sculpture"] was “designed to counter the historical lack of space afforded to Black artists and Black people in cultural institutions.”

The presentation also features never-before-seen works from Abloh’s outstanding archive alongside a humongous, “social sculpture” that offers a space for creative, like-minded individuals to get together and create whether it’s programming for performances, workshops, etc. The immersive piece itself is “designed to counter historical lack of space afforded to Black artists and Black people in cultural institutions,” as per a statement by the Brooklyn Museum.

To learn more about Abloh’s undivided attention to objects and unfaltering patronage to minimalist design, we chatted with the show’s curator Antwaun Sargent and Braun’s director of design and technology, Benjamin Wilson, to discuss key takeaways from the exhibition that is currently on view through January 29, 2023. Check out the exclusive interview below.

Tell us about the connection you have with Virgil and your curation for “Figures of Speech.”

Antwaun Sargent: Virgil had so many ideas. When we were getting to know each other at the very beginning, it was really overwhelming — his ideas were overwhelming, in a sense. I was like, okay, well, these are all great ideas, but which ones of them should make it into an exhibition? And because an exhibition has to tell a story, right? Even if an exhibition’s point is not to tell a story, it has to have some sort of rhyme or reason to it.

How is this exhibition different from previous iterations?

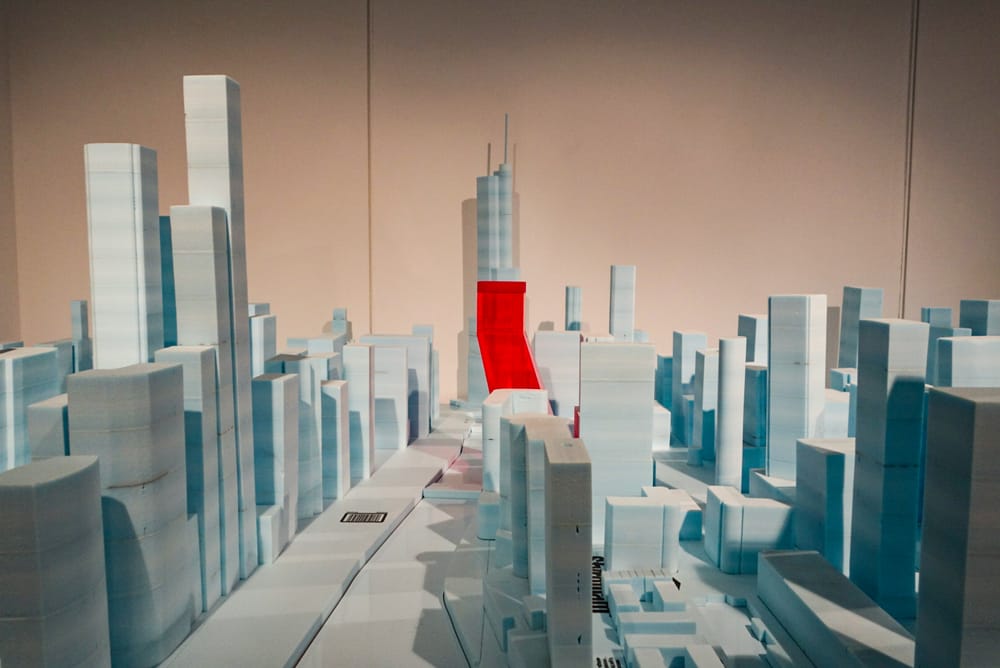

AS: New York was the place where he became sort of a solo artist. Before he came to New York and met Shane, Ian, Venus and all of those folks, he was embedded in Kanye’s creative world in Chicago. Him and Kanye, obviously, were still super tight. But in NYC, he sort of branches out, right, with Been Trill and all of his interests unique to New York, right? For him, he wanted to do something different in New York especially with this “Figures of Speech” exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum. This show is totally different from the original one at MCA Chicago. Like the work tables with all the various objects beside each other, the “Social Sculpture,” and also the gift shop. He wanted the show to follow a sort of logic around minimalism while creating objects made of materials that are simple as way to sort of say that you can also go to Home Depot, get the foam or wood or anything really and make whatever you want to make.

It’s clear that Virgil’s focus on materiality was important to him while offering modes of accessibility in anything he touches.

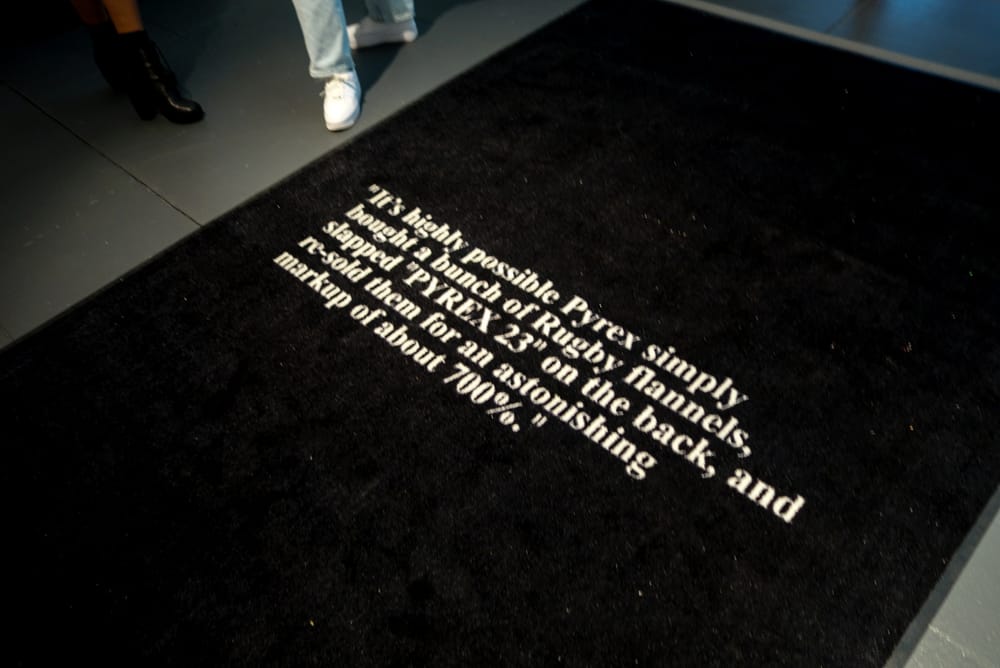

AS: Materiality was super important to him. Like his collaboration with Jacob the Jeweler that focused on office supplies, it was a series that referenced when he was kid making chains with paper clips. In his work, there was a great sense of play, but also generosity in the materiality. And even just like his display method, right? Like people can walk up onto the objects and get up close and personal with them.

And then with the social sculpture, like, all his homies and young artists are going to program it. They’re going to make their own museum within a museum. And so even in sort of taking the space for himself, he’s creating space. And that’s the story of Virgil’s outlook.

“Virgil wanted everyone to feel like they were considered.”

The gift shop is also totally different from the one in MCA Chicago. There’s video art right next to it and the commingling of these objects. Can you talk more?

AS: He calls his shop Church and State, right? Because he sees no separation. They’re separate, but equal in that way. And so with every exhibition, it’s really all about care, right? And it really was about care in the sense that he wanted the audience to feel like they were getting something special. So special to the face that the guards are wearing unreleased Nike products that he made for them, right? Virgil wanted everyone to feel like they were considered. That sort of consideration or care in organizing is one of the guiding principles of who he was. You see that in the Louis Vuitton “Cloud” jacket with the couture beading, you also see that in the Serena dress and you also see that in his sketches. As a young artist, before he had any clout or anything, he was meticulously drawing out his ideas. I hope that’s one of the things that people see. He operated with a tremendous amount of consideration and care.

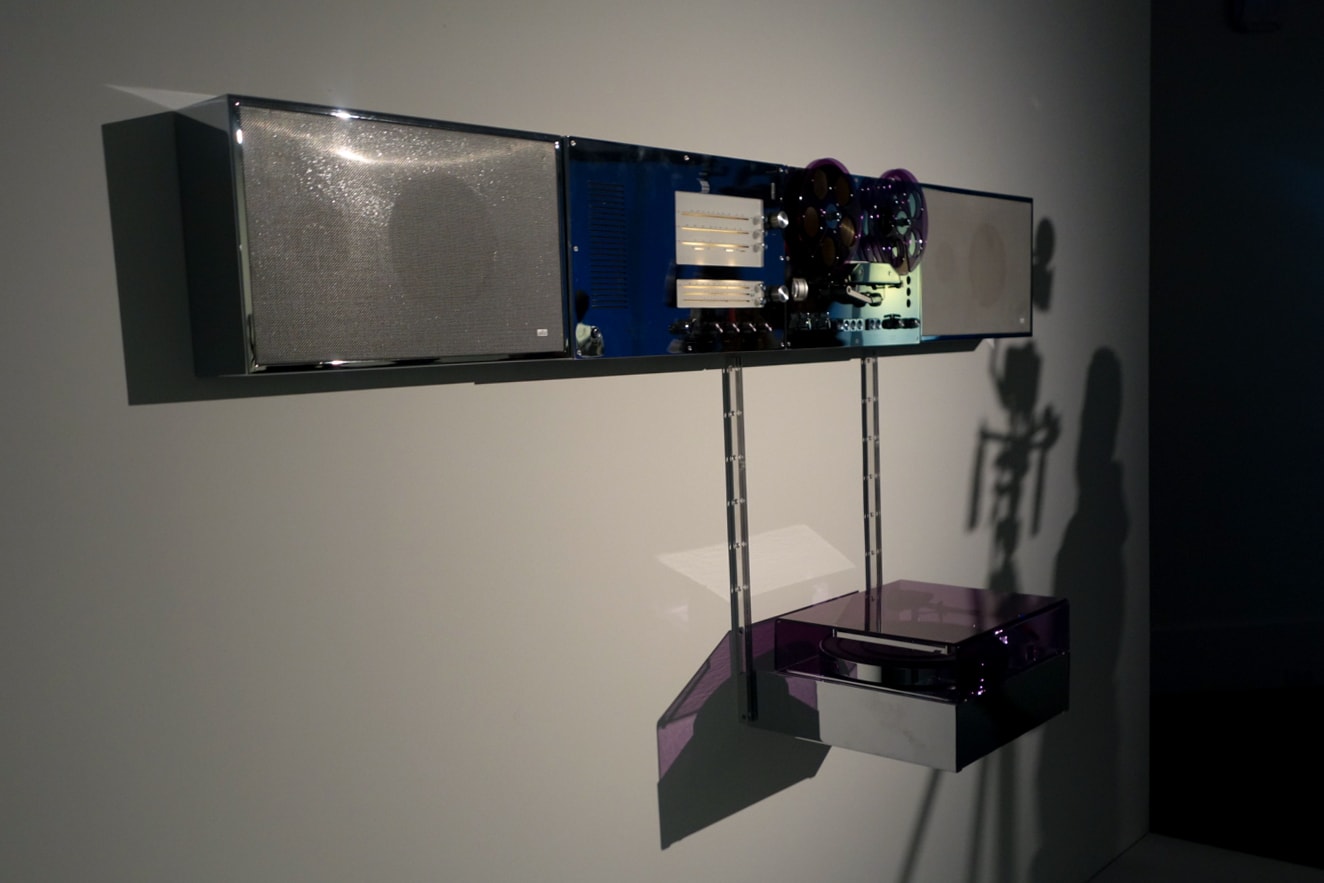

When I was talking to Ben from Braun about the wall mount sound system, he mentioned that Virgil had rule of adding just 3% to something — to show off the beauty of the original design and letting it be celebrated as is.

AS: That’s 100% right. Virgil never saw his collaborative design for that Braun sound system completed. He died before the whole project was finished. Ben from Braun, Tawanda from Alaska Alaska and all the design heads wanted to fulfill Virgil’s purpose for the work as something that anyone can interact with so people can appreciate it without them knowing the history behind it. He also wanted to add Houston’s slab culture to it by adding a chrome finish and candy-colored aspects like the purple touches, you know? It’s an homage to hip-hop as a whole. Then, the 45-minute mixtape is a mixture of sort of Houston hip hop and jazz. The work is a testament to Virgil belonging to different worlds by merging the canon of European modernism with Black, hip hop cues.

Hey Ben, what was it like for you to collaborate with Virgil and the museum?

Benjamin Wilson: As with most of Virgil’s projects, I worked very closely with his design team at Alaska Alaska to Wander, as well as Antwaun Sargent from the curation process for the museum. It was a really great back and forth. The ‘Functional Art’ wall unit we created wasn’t featured in the original “Figures of Speech” exhibition at MCA Chicago. So, it’s a lovely new addition to the exhibition layout at the Brooklyn Museum. It’s one of those works that doesn’t change anything, but it adds to something — it becomes a new part of the dialogue and the collaborative process.

What was it like working with the Brooklyn Museum?

BW: Working with the Brooklyn Museum was really all about finding what the object needed and installing it so it has the right presence, the right space. It’s one of those objects which is meant to be installed in a home, so it needs a sort of living room space. Also we needed to keep in mind the fact that it’s going to be playing a playlist that Virgil put together. The collaborative process, in regards to the unit itself, goes back to about 2019 when I flew over to Chicago with a couple of our partners to meet up with Virgil.

What’s the story behind the ‘Functional Art’ Hi-Fi Unit?

BW: The wall unit itself was a collaborative process as part of our 100 year anniversary. So Braun’s basically turned 100 years last year in 2021. And we were looking for partners who can help drive a dialogue and who better to drive a dialogue with than Virgil Abloom? The guy is writing the book on “Figures of Speech” and changing narratives — he’s redefining things that you might see something different than I do in that one object because of our backgrounds: I’m from Australia and you’re from the US. For example, Virgil’s Chicago imagery of chrome wheels. I see chrome wheels a little bit different than he does. And I’m not sure if I know how you see chrome wheels, but the idea of the different narratives in objects is something which we really wanted to talk with Virgil about.